Still Feel Bad at Composing Even After College? Here’s Why

You hear it repeatedly from composers: “I always feel like a beginner whenever I start a new piece.”

I’ve certainly felt this way before — but I’ve stopped believing these feelings are unavoidable.

What I’ve come to see in myself and my students is that these insecurities arise from two compounding errors.

These errors lead us to ignore the strategies that ensure we can compose reliably, efficiently, and confidently. They are:

We oversimplify our ability to compose as consisting merely of mastering certain techniques.

When we think of “inspiration,” we conflate meaning with motivation.

As a result, we rely too heavily on motivation (in the form of “inspiration” or “deadlines”) to get ourselves to compose while also underutilizing our abilities.

Let’s examine those two errors in more detail — then look at the solutions behavioral science offers.

Error 1: Oversimplifying Your Compositional Ability

Many of us view composing as a collection of specific compositional techniques. For instance,

How to transcribe the sounds you hear in your head or from recordings . . . including intervals AND chords AND rhythms AND melodies . . .

How to harmonize a melody . . . using common-practice harmony OR jazz chords OR pitch-class sets . . .

How to write idiomatically . . . for any of the 4-dozen or so common musical instruments . . .

This list doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of techniques that competent professionals know. Knowing a broad collection of such techniques is essential if you have any aspirations for your music.

However, even if you’ve mastered every common compositional technique, this list would still be missing many of the many of the most essential composing tasks.

Here’s why:

Despite being commonly framed as “how to,” these techniques tend to focus on the “what” of composing, not the “how.”

Unfortunately, compositional techniques do not come labeled, “I am correct tool for artistic problem W or situation X, but not for artistic problem Y or situation Z.” Hence, we cannot summarize our ability to compose in the number of styles or techniques we’ve learned.

Instead, our actual ability to compose consists in how we’ve mastered the process of using these techniques and identifying the relevant situations in which they can be used to solve specific creative problems.

Error 2: Conflating Motivation and Meaning

I wrote about this misunderstanding of inspiration in my previous blog post. To summarize:

The muse is “a guest who does not care to visit those who are indolent.”

— Tchaikovsky

For most creators, myself included, inspiration is a mixture of both motivation and meaning. It refers to:

- What I care about and why

- How deeply I feel about it

- Why I believe others would care about it, too

It’s easy to feel motivated to write when you have ideas you care about deeply — but the passion you feel for your good ideas is not the same thing as the ideas themselves.

Likewise, just because you don’t yet feel passionately about an idea doesn’t mean it’s bad or uninspired. Most often, it simply means you haven’t refined the idea yet.

Here’s the hard truth: You usually have to refine your idea first, before the excitement comes.

This is part of what Tchaikovsky meant when he said the muse is “a guest who does not care to visit those who are indolent” (quoted in Harvey, Music and Inspiration, 74-75).

The Relevant Behavioral Science Models

If you relate to these errors, understanding the behavioral science of why we act can help you overcome them.

Behavioral scientists consistently affirm that when we take any action, it is because we have both the motivation AND the ability.

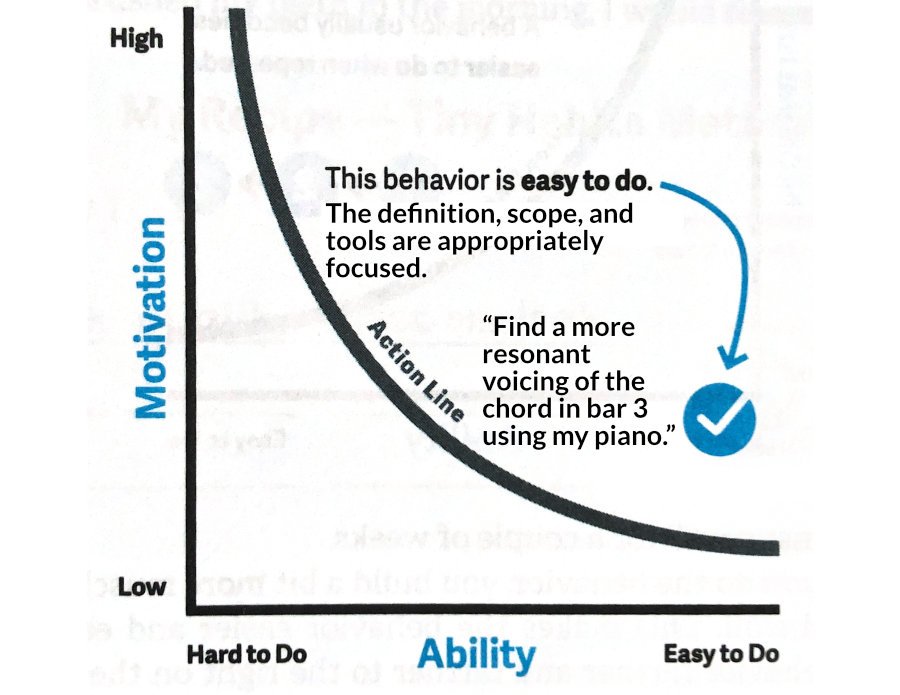

The Fogg Behavior Model

In his book Tiny Habits, researcher B.J. Fogg expresses this idea as a formula (20):

Behavior = Motivation + Ability + Prompt

He later visualizes it as a chart (279, see right).

The X-axis maps your Ability to do a task, and the Y-axis maps your Motivation to do that task.

“There’s a relationship,” Fogg explains, “between motivation and ability. [The curved green line], called the Action Line, shows that relationship.

“If someone is anywhere above the Action Line when prompted, they will do the behavior. . . . However, if they are below the Action Line when prompted, they won’t do the behavior” (279).

Authors Kerry Patterson et al. express a similar idea in their book Influencer. They explain that our behaviors are influenced across 6 dimensions, which can be summarized in the following matrix:

Patterson et al.’s model of influencing behavior

“Where most of us apply a favorite tool or two to our important challenges,” they write, “[skilled creators] identify all of the varied forces that are shaping the behavior they want to change. . . . According to our research, by getting [the] six different sources of influence to work in their favor, [creators] increase their odds of success tenfold” (14, italics in original).

So how do these two behavioral models apply to composing?

Solution 1: Broaden How You Understand Your Abilities

When Fogg talks about “ability” in Tiny Habits, he’s referring to more than just those techniques which are “beyond your skill level.”

Rather, you may lack the ability to do a compositional when it is:

Too large in scope

Too vague in definition

Too hard without the right tools and resources

Some combination of the above

To give yourself the best chance of success, you need to broaden how you understand your Personal Ability (in Patterson’s terms). This can include:

Breaking your creative problems down into smaller tasks

Defining the tasks more specifically

Using the full range of tools and resources at your disposal

Likewise, Patterson et al. show that ability has more dimensions than what you personally can do. You also need to consider how your community and your environment enable you to compose.

You can harness your Social Ability (social capital) in composing by:

Hiring assistants (the classic Hollywood solution)

Working with composition teachers

Seeking feedback from trusted peers and mentors

You can leverage your Structural Ability (environment) by:

Creating a workspace that encourages composing and discourages distractions

Finding the analog and digital tools that work best for you (rather than what your teacher or some internet troll with a stick up his butt said “real composers” “should” use)

Identifying the times of day and contexts in which you work best and feel most creative

Solution 2: Focus on These Broader Abilities, Rather than Your Motivation

According to Patterson et al.’s model, most composers rely on Personal Motivation (“inspiration”) and Structural Motivation (“deadlines”) to get themselves composing. They then use a narrow definition of Personal Ability (“compositional techniques”) to get them across the finish line.

Fogg’s behavior model shows why it is crucial to define your composing abilities more broadly: “The problem is that motivation is often fickle,” he explains (42).

Fogg gives multiple reasons why relying on motivation is a losing ticket for better composing:

Figure 1: Underutilizing your abilities

Your motivations are complex and sometimes compete with one another

Motivation is difficult to maintain at high levels for long periods

It comes (and goes) in waves throughout the day

It works poorly for abstractions and aspirations

Though “motivation is unreliable,” Fogg concludes, “Luckily, ability is not.”

“By looking at where our ability lands on the Behavior Model, we get a good idea of what behaviors are more or less likely to [happen]” (76).

Figure 2: Leveraging your broader abilities

This is where the expanded abilities we identified in “Solution 1” can really help you.

Take the following example: You sit down to compose with middling to low motivation — but all you know you is that you “want your piece to sound better.” (see Fig. 1 right)

The behavioral model (and your lived experience) easily predicts that it’s unlikely this task will get you composing for long (if at all).

In contrast, if you use the ideas that Fogg and Patterson identify — narrow the scope, use your tools, etc. — you can set yourself up for success. (Fig. 2)

Want More Help Applying These Tools?

There’s a lot more that could be said about how to identify these behavioral science ideas to your compositional process.

That’s why I’m put on FREE creative process workshops for composers.

The latest runs January 16-20, 2023, and focuses on writing orchestral music.

By the end of 5-days, you will have learned reliable, new creative tools and completed at least a minute of orchestral music.

Get all the details and sign up below.