Do You Need Inspiration to Write Good Music?

Do you need inspiration to write good music?

Many composers say they do.

They say they struggle to get started unless they have a “good idea.”

I’ve been in this position myself countless times — but I no longer believe that’s the case.

I changed my tune about inspiration because of one question:

Is “Inspiration” about Meaning? Or Motivation?

👉 “Inspiration” refers to meaning when we intend “the message I’m trying to put out into the world” — in other words, the “good ideas” themselves.

That message could be something extramusical, like a Witches’ Sabbath or a dramatic scenario. It could also be something purely musical (though I would argue that absolute music does not exist).

👉 “Inspiration” refers to motivation when we mean “how deeply I care about that message.”

Writing music we care about deeply isn’t just easy; it feels like something we must do.

In contrast, for instance, when I was a student, I forced myself to write in styles I didn’t care about, because I believed (wrongly) that those styles were what “good composers were supposed to write.” In that context, trying to find the motivation to compose was literally painful.

“Inspiration” as Motivation AND Meaning

For most creators, myself included, inspiration is a mixture of both motivation and meaning. It refers to:

What I care about

Why I care about it

How deeply I feel about it

Why I believe others would care about it, too

But it is precisely because inspiration refers to both “meaning” AND “motivation” that I don’t believe you need inspiration to do good work.

Or more specifically, I think we too often overemphasize the “motivation” part of inspiration and downplay the “meaning” part.

We too often overemphasize the “motivation” part of inspiration and downplay the “meaning” part.

Allow me to let behavioral scientist B.J. Fogg explain why…

The Science Behind How Motivation Leads to Composing

The science of behavior can help us understand why we avoid writing music.

In his book Tiny Habits, B.J. Fogg explains that “a behavior happens when . . . [a] motivation, ability, and prompt come together at the same moment” (20).

The formula looks like this:

Behavior = Motivation + Ability + Prompt

In other words, motivation is only one out of three factors that produce behaviors.

The Fogg Behavioral Model

That’s great news!

Because it means you don’t need large amounts of “motivation”-inspiration to compose.

Here’s why.

According to Fogg, “you can visualize this model (of behavior) in two dimensions” (279).

The X-axis maps your Ability to do a task, and the Y-axis maps your Motivation to do that task.

“There’s a relationship,” Fogg explains, “between motivation and ability. [The curved green line], called the Action Line, shows that relationship. If someone is anywhere above the Action Line when prompted, they will do the behavior. . . . However, if they are below the Action Line when prompted, they won’t do the behavior” (279).

The Real Reason You Cannot Compose Without Motivation

In other words, that chart contains the secret to why you cannot compose without motivation:

You are blaming motivation for what is really a lack of ability.

Let me be clear: This does NOT mean you’re a bad composer. It means that the specific task you’re trying to accomplish is either:

Too large in scope,

Too vague in definition,

Too beyond your skill level,

Too hard without the right tools and resources, or

Some combination of the above

For instance, you may struggle to harmonize a melody if you are imagining intricate harmonies, but you lack thorough ear training with chord extensions or pitch-class sets.

In this scenario, among the actions you might take, you might

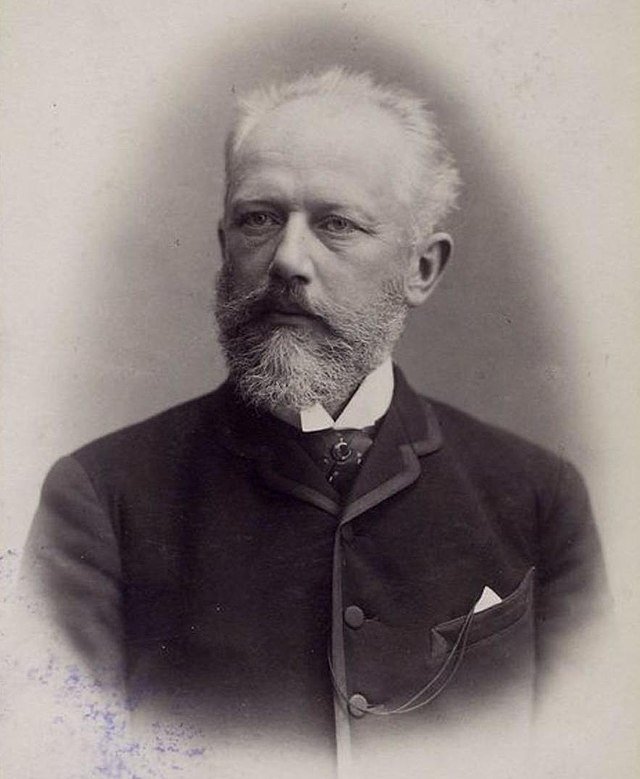

Tchaikovsky noted in his diary that he “worked without any inspiration, but successfully.”

Try working out only one chord at a time (i.e., shrink the scope)

Systematically rule out certain chord qualities (i.e., define the problem better)

Improve your ear training (i.e., grow your skills)

Use a piano (i.e., tools and resources)

Each of these adaptations of the task at hand increase your ability to accomplish it.

In turn, they lower the motivation required for you to do it.

This is why Tchaikovsky could write in his diary that he “worked without any inspiration, but successfully” (in Music and Inspiration, 74).

His compositional abilities greatly exceeded his motivations. He knew exactly how to do what had to be done.

The Creativity Hack To Composing With Little Inspiration

You, too, can apply this hack to your composing.

When your motivation feels weak — and you don’t have the time to improve your skills — you can refocus the task at hand by:

Shrinking the scope of what you’re trying to accomplish

Defining your creative problem better

Giving yourself the tools and resources to make it easier

That way, when you are feeling uninspired (“without motivation”), you can still work “successfully” like Tchaikovsky.

Having now discussed all about the “motivation” part of inspiration, the “meaning” part will be the subject of another post.